Extrapolation Technique Pitfalls in Asymmetry Measurements at Colliders

*Katrina Colletti, Ziqing Hong, David Toback, Jon S. Wilson

The George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy

Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77840

*kcolletti1@tamu.edu

- Version 1.0 (Frozen on 2015 September 22)

- arXiv Version 2.0 (Submitted on 2015 December 2)

- NIM Version 3.0 (Submitted on 2015 December 3)

- NIM Reviewer Comment Responses v1 (Last updated on 2016 March 29)

Abstract

Asymmetry measurements are common in collider experiments and can sensitively probe particle properties.

Typically, data can only be measured in a finite region covered by the detector, so an extrapolation from the

visible asymmetry to the inclusive asymmetry is necessary. Often a constant multiplicative factor is more than

adequate for the extrapolation and this factor can be readily determined using simulation methods. However,

there is a potential, avoidable pitfall involved in the determination of this factor when the asymmetry in

the simulated data sample is small. We find that to obtain a reliable estimate of the extrapolation factor

the number of simulated events required rises as the inverse square of the simulated asymmetry, which can

mean that an unexpectedly large sample size is required when determining its value.

| Number |

Figure |

Caption |

| 1 |

|

Two Gaussian distributions with unit width, with µ = 0.0 and µ = 0.5 in (a) and (b) respectively. We highlight the

events in regions A (−∞, −1.5), B (−1.5, 0), C (0, 1.5), and D (1.5, ∞).

|

|

| 2 |

|

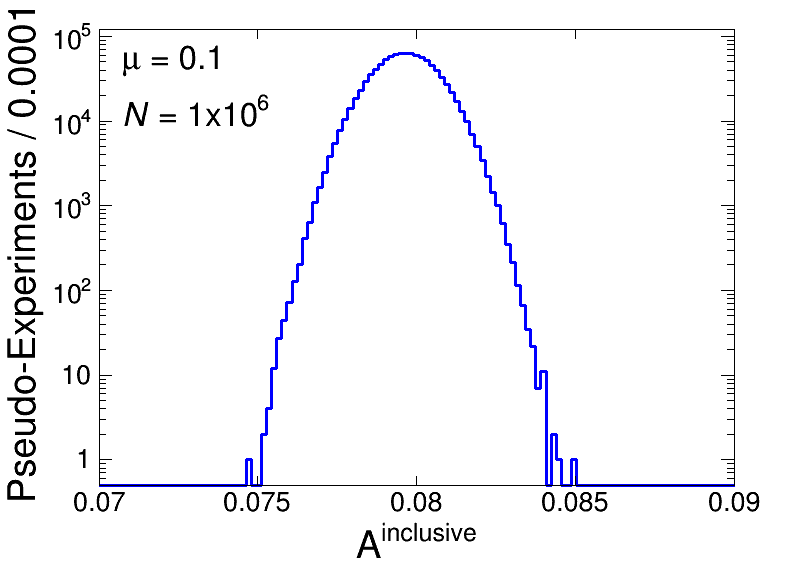

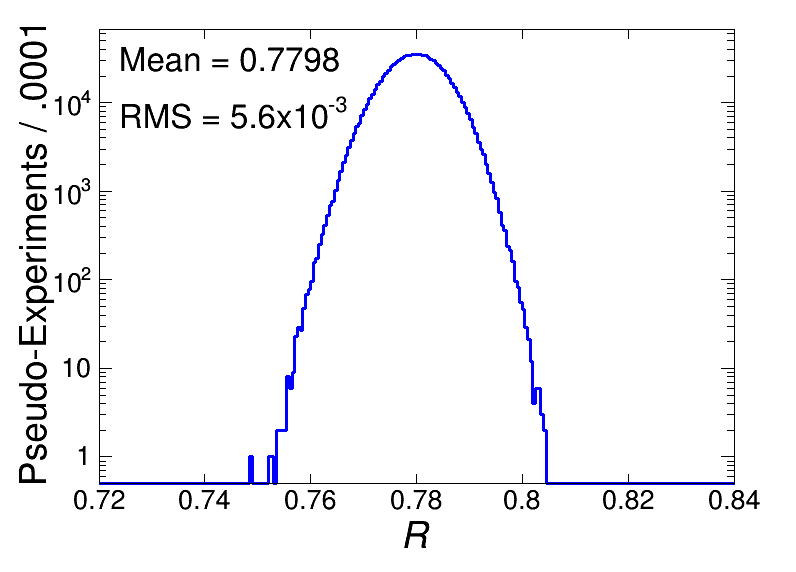

Distributions of Ainclusive, Avisible, and R in (a), (b), and (c) respectively. Each distribution has NPE=106 with N=106 and μ=0.1.

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

Distributions of R with NPE=106 and μ=0.1, for N=105 and N=103 in (a) and (b) respectively. As N decreases, the estimation of R becomes worse; therefore obtaining the correct result with a single PE becomes statistically unreliable, the systematic uncertainty becomes both significantly large and asymmetric. Note the different x-axis scales in both plots.

|

|

| 4 |

|

The same set of plots as in Fig. 3, but for μ=10−3 with N=109 and N=107 in (a) and (b) respectively. We note that the distribution transition also occurs for this μ, but at a larger value of N.

|

|

| 5 |

|

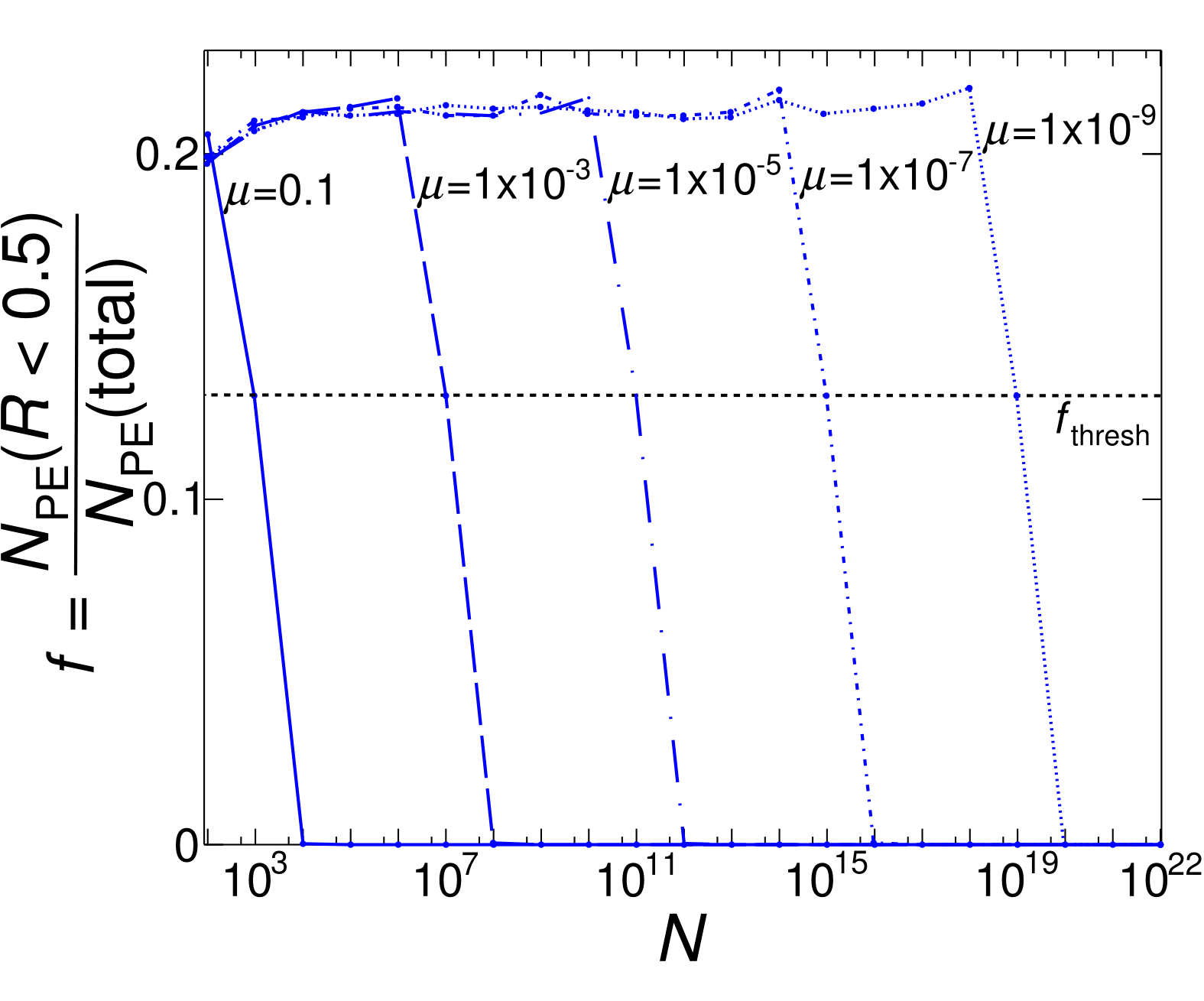

A plot showing f, the fraction of PEs with R<0.5, versus N. Each line represents a different choice of μ varying from μ=0.1 to μ=10−9. We highlight fthresh=0.13, and note that as μ gets smaller, the valeue of N where the line crosses fthresh gets significantly larger.

|

| 6 |

|

A plot of Nthresh versus μ. Note that as μ→0, Nthresh approaches infinity.

|

| 7 |

|

Distributions of R with NPE=106, for various small values of μ. In each case we have selected N large enough such that we are in the high statistics regime to ensure a reliable estimation of R, and we see that R converges to 0.7795 in all cases with small uncertainty.

|

|

|

| 8 |

|

Contour plots of Avisible vs. Ainclusive for NPE=106 and μ=0.02. We have set N=104 and N=106 in (a) and (b) respectively.

|

|

| A9 |

|

A plot of R determined analytically as a function of μ. We can see here how in the limit of small μ, R=0.7795 and only rises by 0.04% when μ=0.1.

|